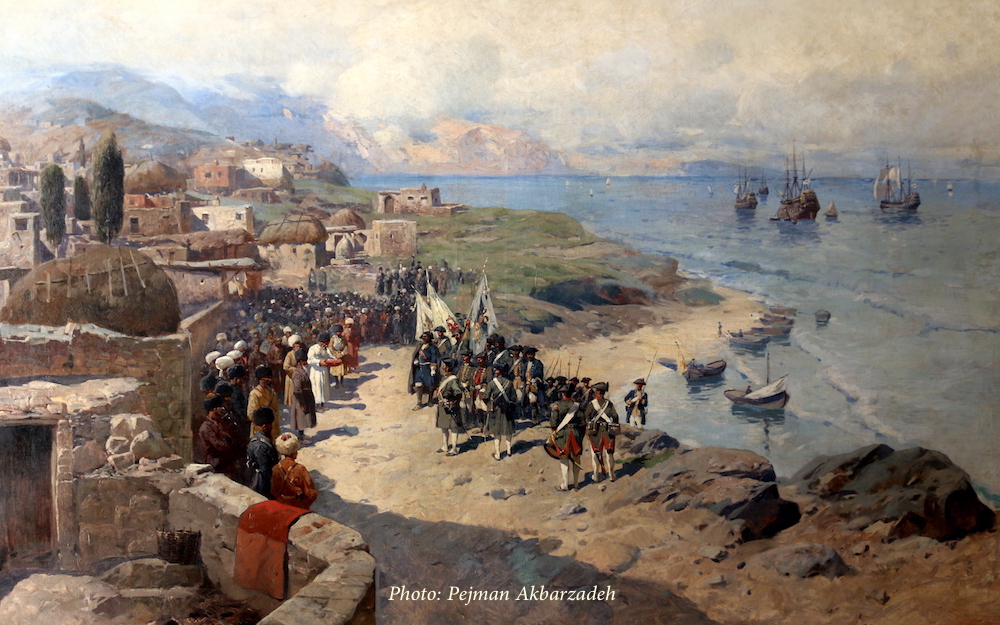

By Pejman Akbarzadeh

Source: BBC Persian TV

Los Angeles is home to the largest Persian community outside of Persia. However, seeing major exhibitions of Persian culture and history in this city is still a rare opportunity. The Getty Museum in Los Angeles is currently displaying over 200 objects from ancient dynasties of Persia. The exhibition has been warmly received but has had a controversial side too.

The exhibition is entitled “Persia“; which is the historical and official international name of Iran until 1935. Although the name was changed by order of Reza Shah in that year, it is still common in foreign languages because of its historical and cultural associations.

“Our collection is very traditional in a way of being Greek and Roman Art. But we feel we need to understand the ancient world in a broader way. So we staged a number of exhibitions to show other civilisations that interacted with Greeks and Romans.” says Jeffery Spier, co-curator of the exhibition. “A few years ago we showed the Egypt and perhaps the greatest civilisation of them all was ancient Iran/Persia. This exhibition tries to show three pre-Islamic Persian dynasties that interacted with the Greeks and Romans; since the beginning of the Achaemenid Empire, established by Cyrus the Great, until the fall of the Sassanians.” Spier added.

Although the Persian Empire is considered the first superpower of the ancient world, general knowledge about it is scant compared to other ancient civilizations, such as Greece and Rome. Parvaneh Pourshariati, an Associate Professor of History at New York City College of Technology, believes “at one point we fell behind, during the Industrial Revolution. Throughout the imperialist and colonialist eras of the early 19th century, the orientalists started to study our languages and do the excavations. But our history was not as important as the history they thought belonged to them, the history of Greece and Rome. Since a certain period, others began to write our history as we had not attempted to do so.”

Among the displayed objects at the Getty Museum, a short sword [akinakes] has generated enormous arguments among archaeologists. This golden sword, attributed to the Achaemenid Artaxerxes I, has never been displayed before. A few media outlets in Tehran have hastily called the sword ‘fake’. However, most archaeologists, while pointing out its differences with similar objects from the Achaemenid era, particularly the design and number of languages carved on the sword, have deferred their final judgment until laboratory examinations. The Getty Museum’s response was brief and siding provide details:

“We have no doubts as to the object’s authenticity but it’s a loan object, not part of our collection, so we can’t speak further to it.”

The Getty Museum has borrowed various objects from North American, European, and Middle Eastern museums for this exhibition. The absence of objects from the museums in Persia/Iran is notable. Iran-US political tensions have affected the cultural-academic exchanges between the two countries.

* The author may be reached by e-mail as pejman.akbarzadeh2 [@] gmail.com

SEE ALSO:

– “Between Sea & Sky”: Blue and White Ceramics from Persia and Beyond” (+Video)

– “Persian Treasure of Dagestan National Museum” (Video)

– “A documentary on Sasanian monument Taq Kasra“

Comment

Comment